Who are Reform UK's 'red' and 'blue' voters? (Part 1)

Reform UK is often painted as a party of older, small-state, Brexit voters — but our research suggests the reality is more complex

Before we begin…

Unchecked UK has spent the last six years mapping the deregulatory landscape — exposing the policies, narratives and actors working to dismantle hard-won social and environmental protections. But with the rise of the Populist Right, the nature of the threat is evolving.

Right-wing populists may present themselves as tribunes of working people, but beneath there often lies a deeply libertarian project — one tied to the interests of big business, not ordinary voters. Although they dress themselves up as defenders of ‘the people’, they simultaneously strip back key protections that safeguard workers, communities, and the environment.

We need to meet this threat. And that starts with having a better understanding of why the Populist Right is having so much cut through, and equally, why progressives are coming up short.

This new initiative — Populism Unpacked — will unpick these questions and explore how those of us who believe in strong protections can counter the false hope offered by populist right politicians. Our aim is not to navel gaze — but to act as a repository of insights and practical advice for those who are acting on this challenge.

This is the first release of our three-part series on Reform UK’s voter coalition — who are they, what do they think about regulation, and most importantly, how can progressives do a better job of reaching them? We hope this provides a useful starting point for effective action. Tune in next week for part 2.

Reform UK is on the rise. Once a fringe successor to the Brexit Party, it is now leading the polls, winning by-elections in Labour heartlands, and shaping the electoral strategies of both major parties.

As its influence grows, so too does the need to better understand its voter base. Who are the voters that make up Reform UK’s coalition? What issues unite them — and where do they diverge? Are they, as you might expect from a right-wing party, animated by libertarian policies, keen to shrink the state and deregulate the economy? And, crucially, are there ways to reach or engage them with the right narrative?

This three part series on Reform UK’s voter coalition (part 2 out next week) brings together the latest polling and focus group data to answer these questions. We find that although Reform UK — and UKIP before it — have often been depicted as a party of older, small-state, Brexit-supporting voters, this view is simplistic and increasingly outdated. In reality, the party draws together a much more complex coalition.

While Reform UK’s leadership may be profoundly influenced by a pro-market agenda – railing against EU regulation or aligning themselves with the interests of global corporations – we find that its voter base is much more complex. Unchecked UK’s polling, for example, found fewer than a third of 2024 Reform UK voters agreed that regulation tends to hold back the economy and intrude on people’s lives. This is hardly an emphatic endorsement of the libertarian worldview.

Recent party interventions indicate a growing awareness of this at the top of the party. In recent months, Reform UK’s leadership has gone to increasing lengths to brand themselves as on the side of working people – whether that’s through pro-union statements or pledges to ‘re-industrialise Britain’ through significant state investment.

Regulation is a particularly useful way of exploring this complexity. Although Reform UK is ostensibly a deregulatory party (frequently decrying the regulatory ‘zeal’ of the EU and the ‘nanny state’), we find that the attitudes of their voters cannot be neatly characterised as on the left or right of this spectrum.

In fact, these voters display far more fluidity in their views, backing measures to regulate large corporations or bring back UK utilities into public ownership – whilst also being the most supportive of Elon Musk’s Department for Government Efficiency (DOGE), for example.

In mapping these complexities, this analysis aims to inform the strategic choices of progressive campaigners seeking to engage, persuade, or contest these voters, particularly those of us making the case for strong social and environmental protections. We hope it provides a useful starting point to consider how we can craft our narrative – and how we respond to the populist right in the UK.

Understanding Reform UK’s voter base

The collapse of the Conservative Party and the rise of Reform

Reform UK began life as the Brexit Party, winning just 650,000 votes at the 2019 General Election and no seats in the House of Commons. For the first few years of the following Parliament, its fortunes changed little.

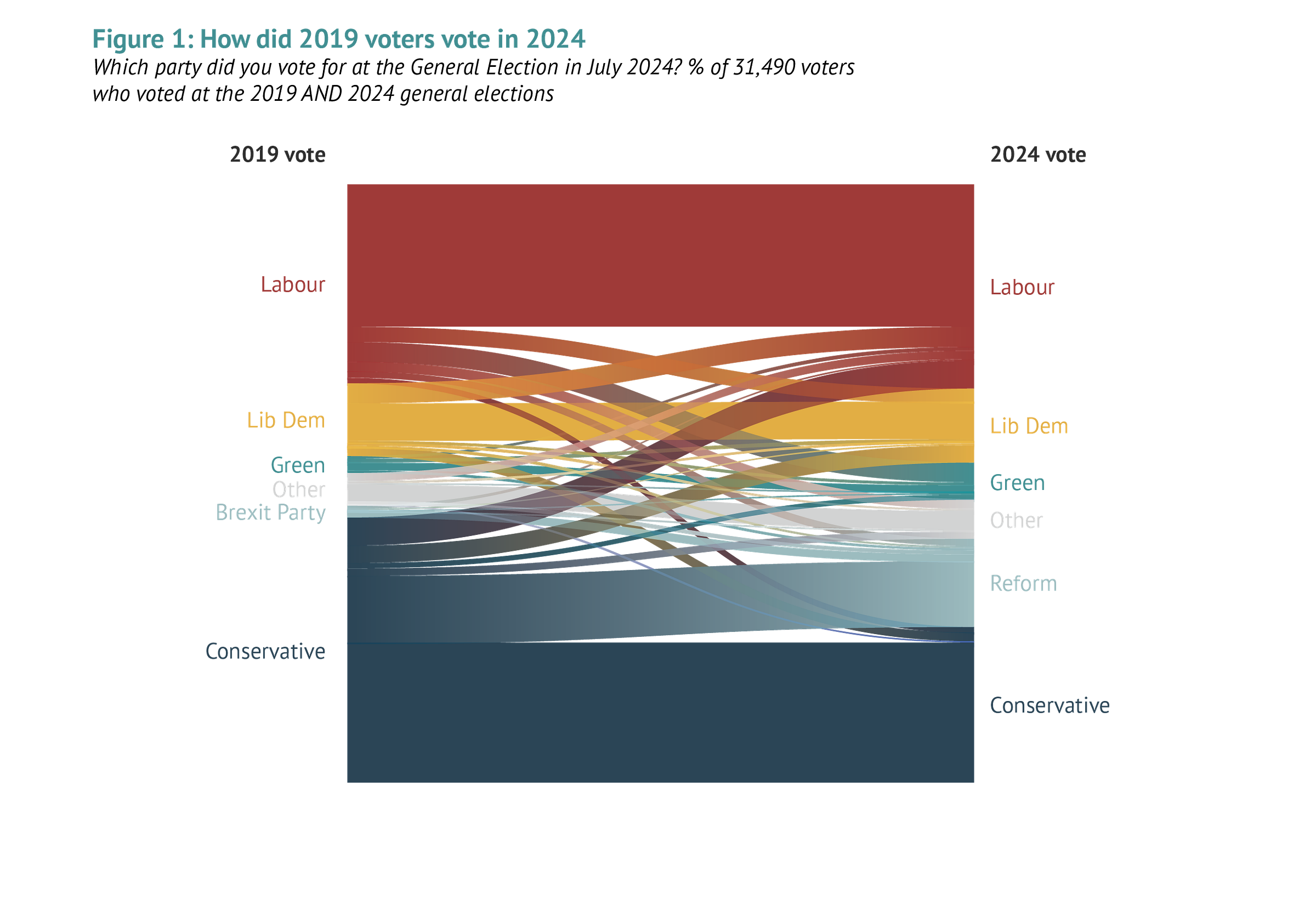

However, as the Tories imploded, this began to change rapidly. With broad swathes of the electorate feeling exasperated by years of scandal and broken promises, large numbers of voters turned to Reform UK. By 2024, they were able to secure over 4m votes – slightly more than UKIP’s all time high of 3.8m in 2015.

The vast majority of these voters – nearly 80% – voted Conservative in 2019. However, this does not necessarily make them natural Conservatives. Many Leave voters began to see the Conservatives as the natural party of Brexit after the 2016 referendum, as evidenced by the large numbers of UKIP voters that backed Theresa May. And so with Johnson’s manifesto pledge to ‘Get Brexit Done’, many Leave voters again opted for the Conservative Party.

The success of Reform UK at the 2024 General Election might be better explained as the return of historic UKIP voters to Farage driven primarily by a breakdown of trust in the Conservatives. Research by academics at Royal Holloway and the University of Portsmouth suggests this is a reasonable interpretation. Their work on the geographic and social demographics of both UKIP and Reform UK argues that the main story is “one of continuity rather than change”. The authors stress that:

“The social base of support for Reform—both at the individual level and constituency level—bears striking similarities to that of UKIP nearly ten years earlier. There is also remarkable continuity between the places that previously backed UKIP and those which now back Reform.”

It is interesting to note that despite all the talk of Farage providing a voice for alienated voters, he did little to persuade non-voters to vote in 2024. The 2024 election saw just 59.9% of the public cast a ballot – the worst turnout since 2001. Reform UK’s success is seemingly far more a story of Conservative collapse than it is about Reform UK’s mobilisation of ‘drop-out voters’.

Since the 2024 election, Reform UK has continued to benefit from the Conservative Party’s challenges. According to YouGov voting intention data, of those that voted for the Tories in 2024, 31% would now vote Reform UK, up from 15% at the beginning of the year. Meanwhile, just 8% of 2024 Labour voters and 8% of Liberal Democrat voters would now vote Reform UK.

The populist coalition – Reform UK’s Blue and Red voters

The stereotype of the party’s base as a collection of disaffected, small state, older Leave voters holds some truth. Reform UK attracts a group of voters who are typically slightly more affluent than the working class and more economically libertarian in their beliefs. They are animated by a desire to shrink the state, are sceptical of income redistribution and benefits, and are opposed to regulating the private sector. They are also deeply socially and culturally conservative, especially around immigration.

A typical voter from this group is a small business owner, most likely retired. They could be self-employed tradesmen or a market trader, for example. What is important about this group often holds highly individualistic beliefs, rarely seeing the state as the answer to problems across society.

These are voters sandwiched between the working and middle classes, a group which, as the natural home of Margaret Thatcher, has always been a bedrock of support for small state (although not necessarily libertarian) thinking. Indeed, Reform UK voters are almost as likely as Conservatives to think Margaret Thatcher had a positive long term impact on the country. As per YouGov’s original categorisation of UKIP voters, they could be referred to as ‘Blue Reform’ voters.

However, all political parties bring together diverse beliefs, and Reform UK’s coalition is no different. As we will explore in greater detail, the party also attracts a proportion of voters with what could be described as more traditional working class attitudes. These voters value a strong state and believe in redistribution and the need for robust regulations. This segment of the Reform UK coalition could be labelled ‘Red Reform’ voters. These voters are most likely part of the roughly 25% of 2024 Reform UK voters who have voted for Labour in at least one election since 2003.

This complexity to Reform UK’s voter base bears many strong similarities to the dynamics within UKIP. Research from 2015 concluded that the party was primarily “an alliance between the working class and the self-employed (and employers), rather than a party of the disadvantaged.” Part of this working class base, the research argues, came from ex-Labour voters who had felt alienated from the liberalism of New Labour, and began to search for alternative vehicles for their social conservatism.

A useful way of exploring this key rift is to look at the attitudes of Reform UK voters towards regulation of the private sector. Polling shows they are fairly split as to whether more regulation on businesses is generally in the interests of ordinary people. 33% say it is not, while 20% say it is. This divide could be explained as the Blue Reform voters interpreting it as meaning further regulation on their small business, while the more working class segment likely interprets the regulation of the private sector as meaning further protections for workers against exploitative employers.

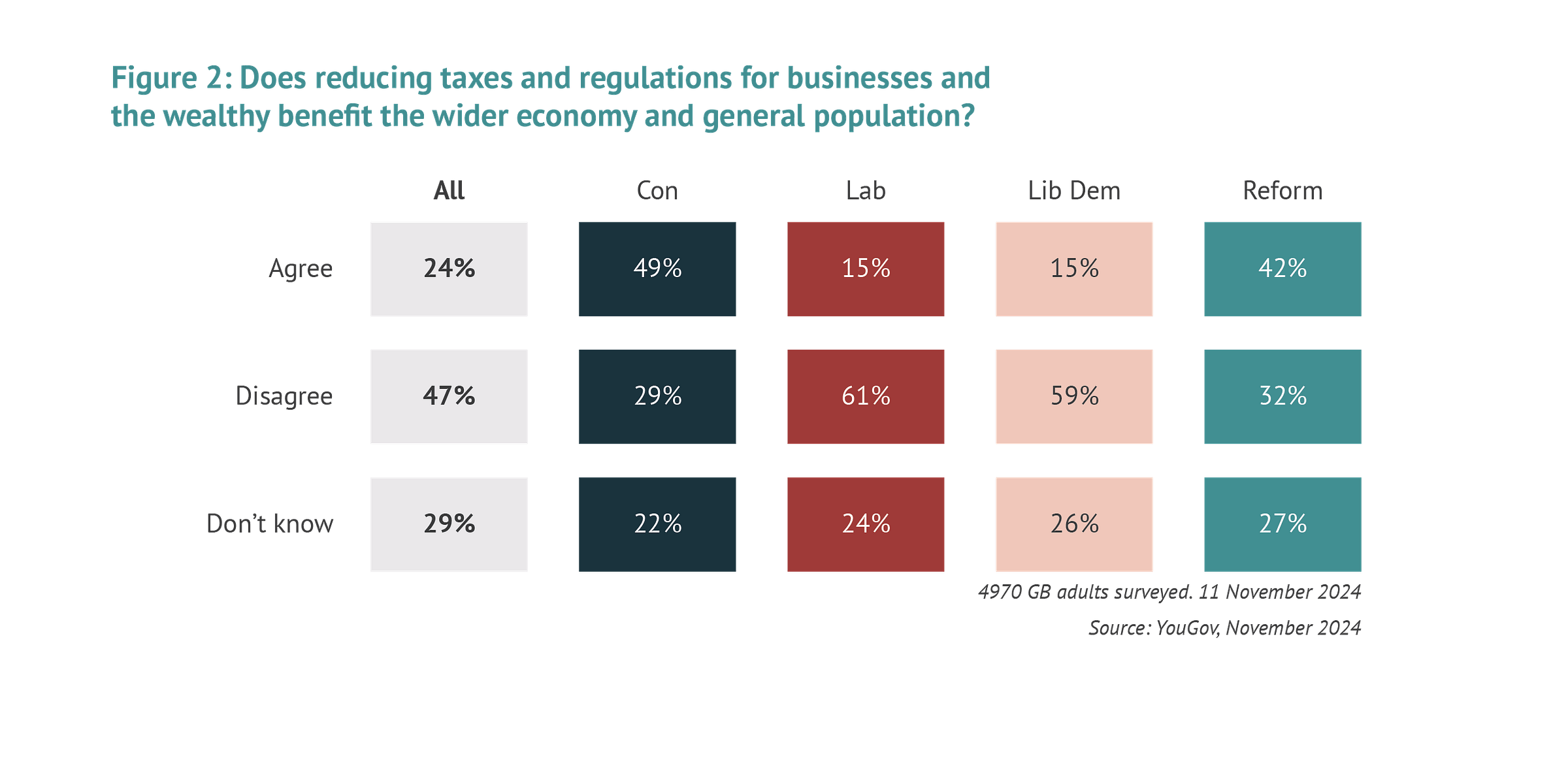

YouGov polling from November last year confirms a similar dynamic. When asked whether reducing taxes and regulations for businesses benefits the wider economy and the general population, 42% of Reform UK voters said it does, compared to 32% that say it does not (see Figure 2). This puts them far closer to Conservative voters than it does Labour and Lib Dem voters, and again underscores the internal tension within Reform UK.

This is perhaps why, despite the image of Farage’s party as turbo-charged Thatcherism, he has often shown such ideological flexibility. Ahead of the 2015 General Election, he echoed Labour’s criticism of zero hours contracts, promised to scrap the bedroom tax and even campaigned to ‘protect your benefits’ during the Wythenshawe by-election. This leftward turn put UKIP much more in step with European populist parties, which often campaign on platforms offering strong economic and social protections. Reform UK’s recent pivots in relation to welfare and trade unions begin to make far more sense within this historical context.

Splitting Reform UK into blue and red camps is, of course, crude. However it is important to recognise that the party has a faction – as did UKIP before them – that is not animated by promises to strip back the state or deregulate the economy. This is where the opportunity could lie for progressive campaigners, including those who advocate for strong protections.

Next week we’ll be releasing part 2 of this analysis, taking a more in depth look at what unites Reform UK’s coalition, and where the cracks begin to emerge. Keep your eye out for our update.